Treponema pallidum

Culture Medias

About

Treponema pallidum, belonging to the family Spirochaetaceae, is distinguished by its unique helical or spiral structure. This bacterium is responsible for syphilis, a contagious sexually transmitted infection prevalent in humans.

Characteristics

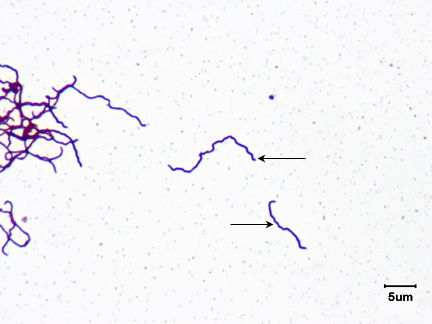

Treponemes are delicate, spiral-shaped bacteria around 6-14µm long and 0.2 µm wide. Their unique morphology includes tapering ends and an unusual midpoint bend. They require dark-field or phase-contrast microscopy for visualization as they are too thin for a light microscope. Fluorescence staining or silver impregnation methods are necessary for staining these bacteria. They possess 3-4 periplasmic flagella, allowing motility and facilitating tissue invasion. These flagella are highly antigenic, inducing early antibody responses. As anaerobic or microaerophilic organisms, they need minimal oxygen and are highly sensitive to environmental changes. Pathogenic Treponemes are obligate intracellular parasites and are solely propagated in susceptible animal hosts, specifically rabbit testes. All Treponemal infections originate from humans, indicating their unique adaptation to human hosts.

Manifestation

The classification of pathogenic treponemes primarily hinges on the distinct diseases they instigate. There are four subspecies known to cause diseases in humans: 1. Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, responsible for venereal syphilis. 2. T. pallidum subsp. pertenue, causing yaws. 3. T. pallidum subsp. endemicum, which leads to endemic syphilis. 4. T. carateum, the causative agent of pinta. The transmission of Treponema pallidum usually starts with penetration through intact or abraded mucous membranes. Venereal syphilis, the most common form, is sexually transmitted while other forms occur due to close non-venereal contact. Acquired syphilis begins when T. pallidum enters through body fluids or via cuts in skin or mucous membranes. This can happen through sexual contact, contaminated needles, or direct contact with a skin lesion. Congenital syphilis happens when T. pallidum infects the fetus either in utero or during birth. Upon entering the host, the bacteria move to the lymphatics and blood, causing systemic infection and metastatic foci. The incubation period is variable, and symptoms appear after 2-4 weeks. About 30% of people exposed to an infected partner develop syphilis. The virulence factors of T. pallidum include endoflagella, promoting tissue invasion and immune response, outer membrane proteins that enable host cell adherence, hyaluronidase that aids perivascular infiltration, and the ability to cloak itself in host cell fibronectin to avoid phagocytosis. In terms of clinical manifestation, syphilis occurs in two forms: acquired and congenital. Acquired syphilis, which progresses through primary, secondary, latent and tertiary stages, can present with a variety of symptoms, including skin lesions, systemic symptoms, and potentially severe complications if untreated. Primary syphilis presents as a single painless chancre, secondary syphilis involves more widespread systemic symptoms and skin involvement, and latent and tertiary syphilis involve a range of systemic complications, including neurologic and cardiovascular involvement. Congenital syphilis, transferred from an infected mother to the child, is severe and often fatal. Overall, T. pallidum is a complex and versatile pathogen with various transmission methods, stages, and clinical presentations. Its success as a pathogen is primarily due to its virulence factors and its capacity to invade various body tissues, leading to a broad range of symptoms and clinical manifestations.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis of syphilis, which is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, involves multiple steps and various types of samples. For instance, lesion and ulcer samples should be uncontaminated, and PCR samples should be collected with sterile swabs, while tissue and needle aspirates of lymph nodes should be kept in buffered formalin at room temperature. When congenital syphilis is suspected, a small portion of the umbilical cord is taken and either refrigerated or fixed in formalin. Serum is the best specimen for serology tests, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is also used for microscopy. Since T. pallidum cannot be visualized under regular light microscopy, darkfield microscopy or fluorescent stains are necessary. The exudate from skin lesions can be examined using darkfield microscopy, while the direct fluorescent antibody test is employed to detect T. pallidum. In the latter test, fluorescein-tagged antitreponemal monoclonal antibodies stain the bacteria, which then appear as bright, sharply defined, apple-green fluorescent color bacilli. PCR can be used to detect T. pallidum in genital lesions, blood samples from infants, and CSF, but this method is usually restricted to research or reference labs. Direct detection of spirochaetal DNA in clinical material via molecular methods may play a crucial role in diagnosing syphilis in challenging or unusual cases in the future. Serological tests for syphilis measure treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies. Non-treponemal tests measure IgG and IgM antibodies developed against lipids released from damaged cells early in the disease and that appear on the cell surface of treponemes. These tests use cardiolipin, derived from beef heart, as the antigen, and they are commonly used for syphilis screening and monitoring treatment effectiveness. The non-treponemal tests include VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) test, RPR (Rapid Plasma Reagin) test, Toluidine Red Unheated Serum Test (TRUST), and Unheated serum regain test (USR). These tests involve the reaction of antibodies with the cardiolipin antigen, and the results are visible through the flocculation of the fluid. The treponemal tests include the Microhemagglutination Treponema pallidum (MHA-TP) test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA), Treponema pallidum–particle agglutination (TPPA), Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS), Enzyme lmmunoassays, Western Blot, and the group-specific test known as Reiter’s protein complement fixation test (RP-CFT). These tests are more specific, as they detect antibodies to T. pallidum itself. Finally, efforts to culture T. pallidum in vitro have been unsuccessful, as this bacterium cannot grow in artificial cultures.