Enterococcus faecalis

Culture Medias

About

Enterococci, including species such as Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium, are gram-positive bacteria commonly found in soil, food, water, and as part of the normal flora in animals and humans. They are particularly prevalent in the human gastrointestinal and female genitourinary tracts. Enterococci can cause infections when they gain access to sterile sites in the body, often during gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedures. They are especially significant in hospital settings, where they can be transmitted person-to-person or via contaminated medical equipment. Enterococcus faecalis is a notable cause of hospital-acquired urinary tract infections and endocarditis.These bacteria have a variety of virulence factors, such as cytolysin/hemolysin, which can lyse red blood cells, and aggregation substances that promote clumping of cells and facilitate the transfer of drug resistance.Treatment of enterococcal infections usually involves a combination of penicillin or ampicillin and an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin. This regimen is typically effective due to their synergistic effect, as penicillin or vancomycin can weaken the bacterial cell wall, allowing the aminoglycoside to penetrate. In cases of resistance, vancomycin is used, and linezolid is an option for treating vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Preventive measures include administering penicillin and gentamicin to patients with damaged heart valves prior to certain procedures. As of now, there is no vaccine available for enterococci.

Characteristics

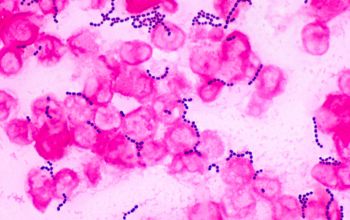

1/ Gram-positive, 2/ cocci, 3/ diplococci, 4/ growth both-aerobic-and-anaerobic, 5/ catalase-negative, 6/ oxidase-negative, 7/ phrase-positive, 8/ vancomycin-susceptible, 9/ penicillin-resistant, 10/ esculin-positive, 11/ bile-tolerance, 12/ NaCl 6.5%-tolerance

Manifestation

Enterococci, due to their intrinsic and increased drug resistance, are primarily responsible for hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infections. They can cause a variety of conditions including urinary tract infections (such as cystitis, urethritis, pyelonephritis, and prostatitis), blood infections (bacteremia), and life-threatening heart infections (mitral valve endocarditis). They may also lead to intra-abdominal, pelvic, and soft tissue infections, eye infections, and rarely, meningitis and respiratory tract infections.

Laboratory Diagnosis

In the laboratory, E. faecalis is typically isolated from samples such as urine or pus from infected sites. Identification relies on cultural characteristics, microscopic observation, and biochemical tests. For precise identification and genetic characterization, molecular diagnosis is also used. There is no special requirement for sample collection, transportation, or processing. I - Macroscopy and Culture: Enterococci can be identified through the following features: 1/ They are gram-positive bacteria, appearing as oval shapes organized in pairs with a distinctive angle between them, resembling a spectacle-eyed look. 2/ When cultured on blood agar, they yield smooth, gray, and typically non-hemolytic translucent colonies. However, α or β hemolysis can sometimes occur. 3/ On MacConkey agar, they generate minute magenta pink colonies. 4/ They show poor growth on nutrient agar. 5/ Enterococci can thrive under extreme conditions, including high salt concentrations (6.5% NaCl), high bile content (40%), high pH levels (9.6), and a wide range of temperatures (10°C to 45°C). 6/ They exhibit heat resistance, surviving temperatures of 60°C for up to 30 minutes. 7/ Enterococci are categorized into five groups (I to V) based on mannitol fermentation and arginine hydrolysis characteristics. E.faecalis and E. faecium are part of group II and can be further differentiated by additional biochemical traits. II - Biochemical tests: They are important for the differentiation and identification of Enterococcus faecalis. To conclusively identify the bacteria as E. faecalis, once it is established as Gram-positive cocci, a sequence of biochemical analyses is performed. Regularly utilized tests include the catalase test, oxidase test, LAP test, and PYR test. The Bile Esculin test, examination of growth in 6.5% NaCl, arginine dihydrolase test, and tests for carbohydrate fermentation (including pyruvate, mannitol, and raffinose) are also commonly employed. Several biochemical tests help differentiate and identify Enterococcus faecalis: 1/ Catalase Test: E. faecalis tests negative, assisting in differentiating it from staphylococci. 2/ Hemolysis: E. faecalis is typically non-hemolytic. 3/ Motility Test: E. faecalis is non-motile. This distinguishes it from E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus, which are motile. 4/ Pyrrolidonyl-β-naphthylamide (PYR) Test: E. faecalis tests positive, enabling presumptive identification of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci and enterococci. 5/ Esculin and Bile-Esculin Test: E. faecalis tests positive (with growth and black precipitate), helping differentiate enterococci from non-enterococcus group D streptococci. 6/ Bile Solubility Test: E. faecalis is insoluble in bile, unlike S. pneumoniae, which is bile soluble. 7/ LAP Test: E. faecalis tests positive, used for identifying catalase-negative, gram-positive cocci. 8/ Pyruvate Broth: E. faecalis tests positive, aiding in differentiating it from E. faecium, which tests negative. 9/ Salt Tol